cephaloPOD19 was the second iteration of the cuttlefish artist camp originally dreamt up by Lichen Kelp in 2018. This edition was curated by both Lichen Kelp (Forum of Sensory Motion) and Danni Zuvela (Liquid Architecture) and was supported by Australia Council for the Arts. The trip was attended by 14 artists in total and took part near Whyalla, South Australia. Our purpose was to witness the spectacular mating displays of the Giant Australian Cuttlefish which takes place in winter each year, with the belief that artists potentially have much to offer the field of marine biology in observing this ritual, so much of which is still not understood by scientists. Being placed in the role of audience for this incredible underwater performance, the artists bring their shared language of colour, patterning, light and movement to the experience and translate it back on shore through their future works. Our home during the camp is pictured here; the Point Lowly Lighthouse and cottages. Image by Keelan O’Hehir.

The trip began with a visit to the Barngala Cultural Centre, Port Augusta, with an introduction to the revived Barngala language dictionary.

More information here. Image by Keelan O’Hehir

cephaloPOD19: Why Listen to Animals article by Danni Zuvela for Liquid Architecture. Image by Lichen Kelp remixed by Jay.

Pattern Flashing, a junior male Sepia Apama, or giant cuttlefish in full display mode in the winter shallows of Spencer Gulf. Image by David Haines.

Days in the water with the cephalopods were followed by extended campfire conversations around cuttlefish, the cosmos, and community.

Image by David Haines.

Cuttlefish apparition caputured midway through Cameron Robbins’ submerged nocturnal lighting performance. Image by Brodie Ellis.

Industrial ambience provided by Santos gas plant which is adjacent to the cuttlefish breeding ground. Image by Keelan O’Hehir.

Michael Candy’s before image of Little Sunfish, his miniature robot replica of the Fukishima submarine navigating through the marine algae of Spencer Gulf.

See excerpts from his film resulting from the FSM x LA cephaloPOD19 residency here

Encounters of the third kind; here one of the Giant Australian cuttlefish - often considered to possess an alien intelligence, meets the robot submarine up extremely close. Image by Michael Candy.

After a morning spent diving with the cuttlefish, two of the artists in residence walk along the beach at Point Lowly, with the looming gas plant, Santos, in the background. Image by Keelan O’Hehir.

Beach cyanotypes workshop in progress with Selena De Carvalho and Michael Candy. Image by Keelan O’Hehir.

Cuttlefish communication being illustrated by camp curators Danni Zuvela and Lichen Kelp. Image by Keelan O’Hehir.

Neptunes balls, discovered on the foreshore; intertidal sea grass washed into perfect examples of geometry in nature. Image by Lichen Kelp.

Michael Candy flys his customised drone around the lighthouse while Cameron Robbins whale watches through binoculars. Image by Brodie Elllis.

The cephaloPOD19 cuttle camp was promptly followed by a second trip for the year; a family edition comprising two families, Lichen Kelp and Dylan Martorell and their two kids and Sarita Galvez and Bryan Phillips and their two boys. Samuel Galvez pictured here with a dead cuttlefish that had washed ashore in near perfect condition.

David Haines image of his light drawing (I see a cuttlefish!) against the industrial backdrop of Whyalla.

A cuttlefish dissection being lit up in multi coloured disco lights. The Sepia Apama cuttlefish, the species that congregate en masse in Point Lowly, Whyalla each year, live an intense and short life. For most of the year they live a solitary life around the coat of Australia before travelling a great distance to mate and spawn and die off. Hence by July there are more and more dead ones that can be found floating in the water or washed up along the shoreline. It is thought that this short life span has increased the evolutionary particularities of the species with their huge roster of adaptive survival tricks. Image by Lichen Kelp.

Cuttlefish egg sack and ink visible through the blue light during a dissection that fused science with art and finished with a poetic cuttlefish funeral held by the kids of the second camp for 2019.

Aerial view of Spencer Gulf. Image by David Haines. The mangroves that would have once been much more densely populous are visible in the shallow estuary.

Peter Godfrey Smith, Other Minds; text from the cuttlefish reading group that evolved out of the cephaloPOD19 camp.

Info here;

https://liquidarchitecture.org.au/events/cephalopod-reading-and-learning

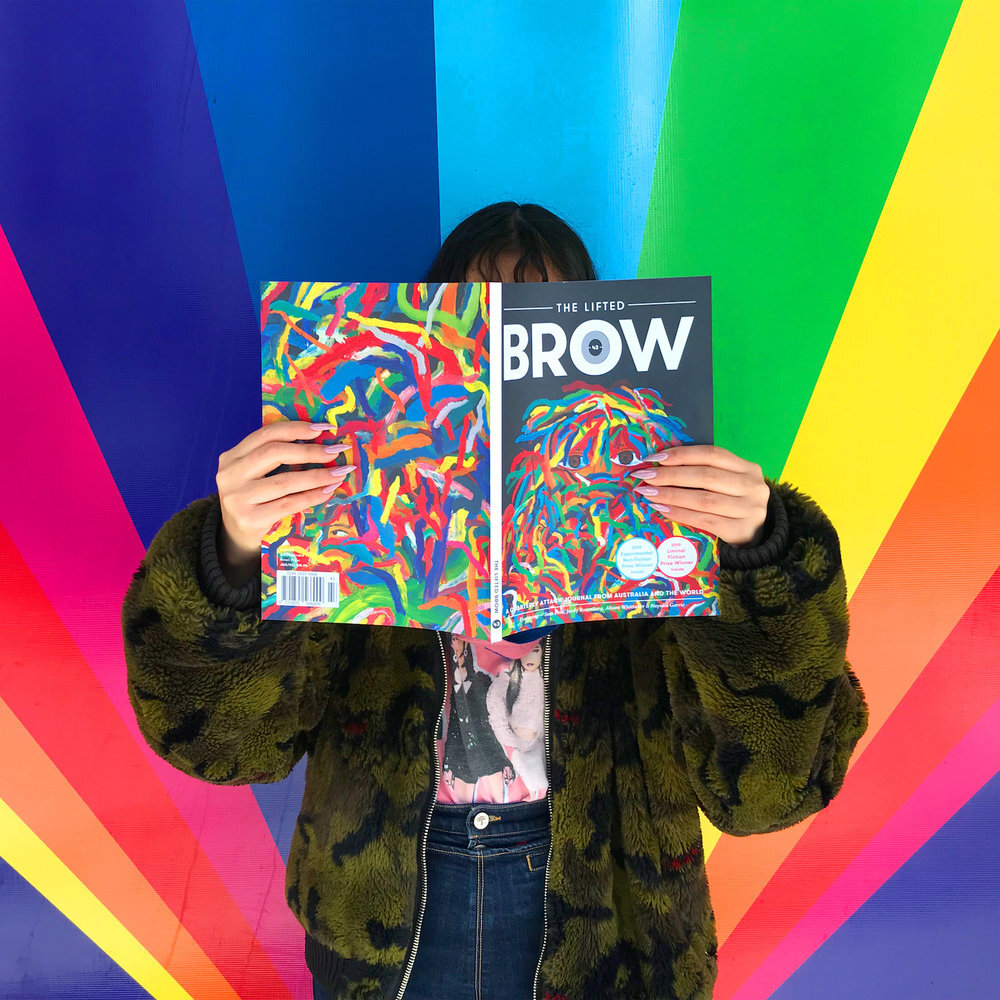

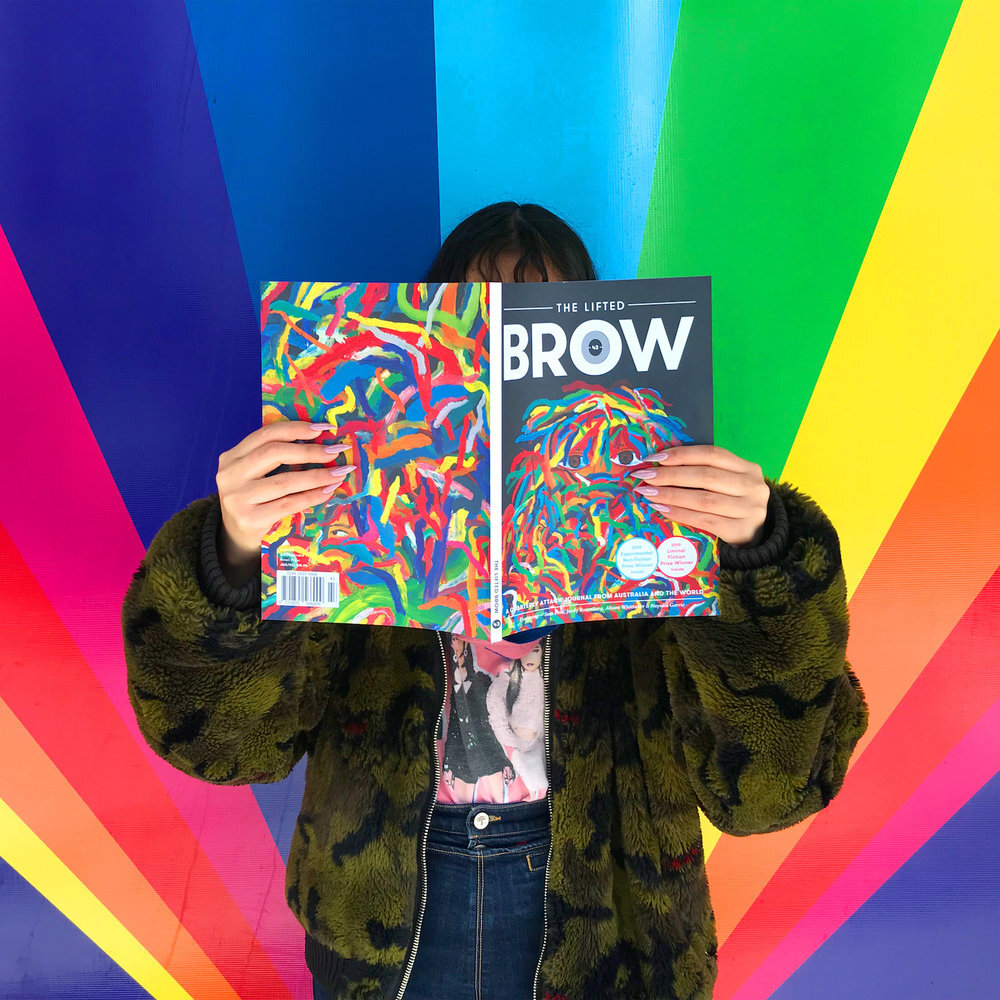

Michael Dulaney’s The End of Dreaming article; part of his regular ‘Environment’ column about the solidarity to be found the Whyalla steel industry and the wonders of the cuttlefish can be found in the latest issue of Lifted Brow. Read here

Still from 'Contact & Witness' by Brodie Ellis from her exhibition Heavy Launch at Linden New Art.

Extract from the accompanying catalogue text;

Ellis’ second video, Contact and Witness, documents the mating displays of cuttlefish. Ellis captured this footage over a number of days filming at Point Lowly in South Australia. The film shows how the cuttlefish are able to signal and communicate by fluorescing and generating intricate variations in the colour and pattern of their skin. They are also able to camouflage themselves perfectly into their surroundings. The cuttlefish’s means of protecting themselves is completely self-sufficient. Their intelligence manifests in their ability to reflect their environment.

We know relatively little about cuttlefish and hence Contact and Witness provides a beautiful example of how much we can still learn about life on our own planet. This work sits in line with a stream of current ecocritical thinking that suggests “recognition of the lives of animals in conjunction with our own animality is indispensable to the creation of ecological sensibilities and ethical orientations that are adequate to the demands of the Anthropocene.”5

Acknowledging and better understanding our vulnerability could be the first step towards environmental sustainability.

5 Deyo, B., “Tragedy, Ecophobia, and Animality in the Anthropocene”, in Eds. Bladow, K. and Ladino, J., Affective Ecocriticism Emotion, Embodiment, Environment, University of Nebraska Press, 2018, p.197.